by NRF User | Apr 30, 2018 | NRF News

Every house has a story to tell, and uncovering that story is like a treasure hunt. Take the time to sift through the records and the history of your property will slowly unfold. You will come to learn more about the history of the structure, its residents, and its role in a larger neighborhood story.

This document contains 3 resources, one general and two specific:

- How to Research Your House in Rhode Island

- How to Research Your House in Newport, RI

- How to Research Your House in Providence, RI

Click here to download the tools you need to research your own house’s history!

by NRF User | Apr 16, 2018 | NRF News

Historic preservationists do not want to freeze time. Preservation is not about resisting change, rather it’s about managing change so that as communities evolve they do not lose their special places along the way. All old buildings – from the plainest barn to the most elaborate mansion, from a 1750s Georgian house to a 1950s ranch house – deserve to be preserved. This is how we hold onto our heritage and keep our community’s character.

Click to download our Historic Homeowner’s Toolkit for a comprehensive primer covering everything you wanted to know about preservation in Newport and Rhode Island!

by NRF User | Aug 29, 2017 | NRF News

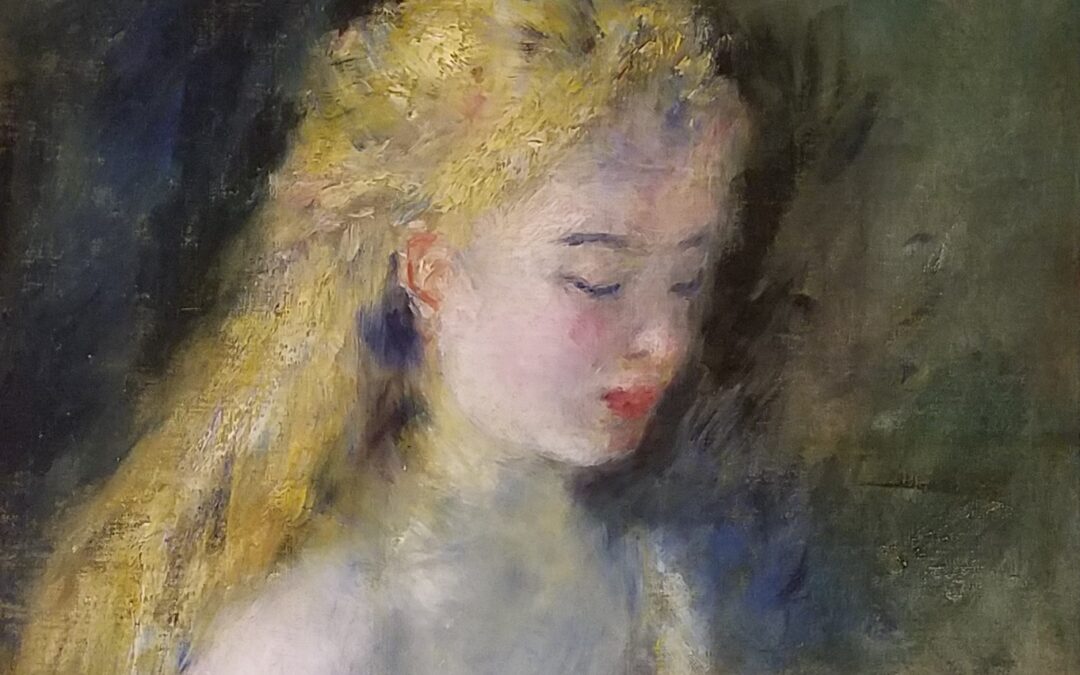

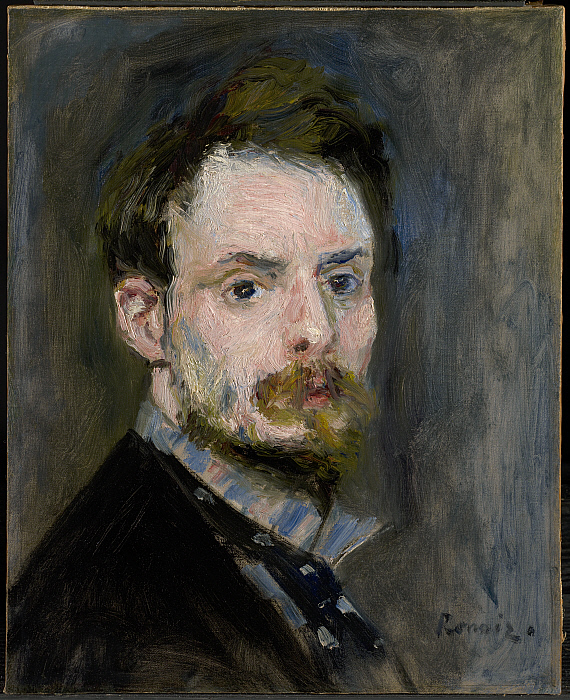

A small painting in a gilded frame hangs above the mantle in Doris Duke’s bedroom at Rough Point. Amidst the splash of yellow walls, bold purple fabrics, and glinting mother of pearl furniture, the painting is unassuming by comparison. This is why visitors are often surprised to discover that it is one of the more precious works of art in the house—a charming scene of a young girl focused on her needlework, painted and signed by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the famous French Impressionist.

Until recently, very little was known about this wonderful, but mysterious, painting in Rough Point’s collection. As this summer’s Laird Graduate Intern in Museum Studies, I’ve had the opportunity to dive deeply into research on both the house and its collection, and I found myself especially captivated by this little painting.

A pair of paintings

One of the most exciting discoveries in my research revealed that our painting is most likely a preparatory study for another Renoir owned by The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. The resemblance between the two paintings is readily apparent. The compositions are nearly identical, with the model—who is now known to be Nini Lopez, one of Renoir’s favorite Montmartre girls—calmly engaged in needlework as her blouse falls gently off one shoulder. Our painting has a loosely worked quality, capturing the artist’s inspiration in the moment.

The period of the 1870s was a transformative time in Renoir’s life and work. Living in poverty and rejected by many critics, Renoir struggled to gain a professional foothold. Even among the other Impressionists, Renoir’s pure colors and broken brushstrokes were not always understood—in fact, Manet once said to Monet that Renoir would never amount to anything.[1] But soon after our painting was completed in 1875, things started to pick up for Renoir. With portrait commissions from wealthier patrons, such as the Charpentier family in 1878, Renoir could now afford to marry and buy a house.[2] His style was also maturing. Renoir’s fascination with girls engaged in needlework continued throughout his career, perhaps stemming from his insistence that his style of painting was tricotage, or knitting the colors together on the surface.[3]

A “poetic symbol” in times of war

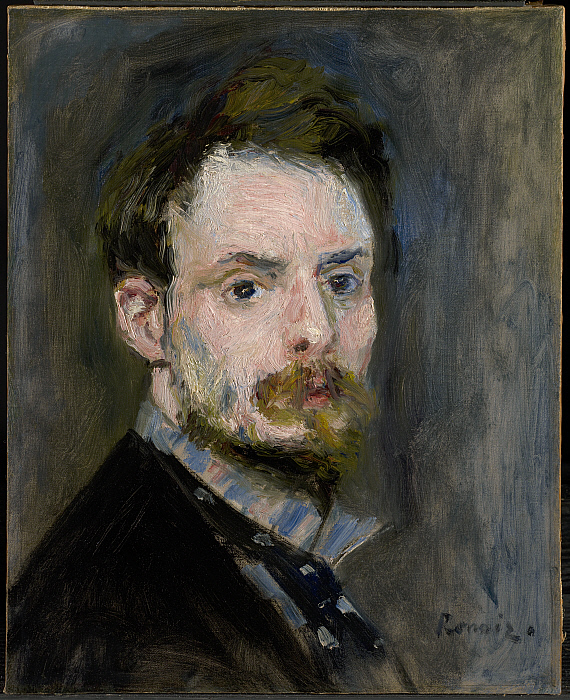

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Self-portrait, c.1875, The Clark Art Institute, 1955.584.

In 1919, the painting was part of a significant collection of nineteenth-century art put up for auction by the estate of its previous owner, Nicolas-Auguste Hazard. Alongside our Renoir were works by other titans of nineteenth-century painting, including Cezanne, Delacroix, Courbet, Gauguin, and Manet—perhaps finally proving just how wrong Manet had been about Renoir’s potential. In a twist of fate, Renoir died on December 3, 1919—the final day of the auction.

By 1941, the painting had passed through several hands and was now part of the war effort. France had fallen to Hitler and organizations formed across the United States to send aid to Europe. One such organization, the Free French Relief Committee, held a Renoir exhibition to raise money for General de Gaulle’s nascent French Resistance.[4] They chose Renoir because 1941 was the 100th anniversary of his birth, and because they believed his art to be revolutionary, “a poetic symbol” of the France that the men and women of the Resistance were fighting for.[5] Our painting appeared in the exhibition alongside eighty-eight other works by the artist. The exhibition closed on December 6, 1941. The very next day, December 7, the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor finally forced American involvement in World War II, which eventually led to the liberation of France and the end of the war.

Home at last

Like Renoir, Doris Duke had a zest for life. She acquired the painting in 1957 and later installed it as the only painting in her bedroom, where its bright, vivacious colors perfectly complemented the eclectic, bold design of the room. Today, Jeune fille blonde cousant remains a cherished object in the Rough Point Collection, delighting visitors with its soft, dream-like quality—the hallmarks of Renoir’s style which make it such a pleasure to behold.

Photograph of Doris Duke’s bedroom, Rough Point, Newport Restoration Foundation

By Ashley E. Williams

Ashley E. Williams is the Newport Restoration Foundation’s Laird Graduate Intern in Museum Studies for summer 2017. During her summer at Rough Point, Ashley dove deeply into curatorial research and provided support for programming and events. In addition to creating fuller object files for several of our most prominent paintings, her larger research project explored the architectural and public history of Rough Point from 1887 to 1924. This fall, Ashley goes on to her final year at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, where she is earning her Master’s degree in the History of Art and Architecture.

Sources:

[1] R.H. Wilenski, Modern French Painters (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1940), 61.

[2] Ibid., 62.

[3] Renoir: Centennial Loan Exhibition 1841-1941, For the Benefit of the Free French Relief Committee, (New York: Duveen Galleries, 1941), 18.

[4] Coincidentally, the committee included Grace Graham Wilson Vanderbilt, a relative of Frederick W. Vanderbilt who built Rough Point (1887-1891), the painting’s final home.

[5] Renoir: Centennial Loan Exhibition 1841-1941, 11.

by NRF User | May 31, 2017 | NRF News

We are celebrating a family reunion of sorts at Rough Point this season. For the seventeen years that the mansion has been open as a museum, full-length portraits of Nanaline Duke and Doris Duke have hung at the top of the grand staircase leading to our second floor galleries and Doris Duke’s bedroom. Nowhere in the house could you see James Buchanan Duke, who bought the estate in 1922 from Princess Anastasia of Greece and Denmark (the former Mrs. William B. Leeds). Doris Duke might have displayed photographs of her father during her lifetime, but after her death in 1993, all personal documents and photographs were removed by her estate in preparation for the transfer of the mansion and its art and antique furnishings, in accordance with her will, to the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF).

There were painted portraits of James B. Duke elsewhere – at Duke University, the Duke Endowment, and the National Portrait Gallery, but not on view at Rough Point. That is, until now. A fourth painted portrait, by British artist John Da Costa (1867-1931), was given to NRF by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation in 2004 (fig. 1), but darkened varnish and a sagging canvas support had made this portrait unexhibitable when it first came to us, and its original carved and gilded frame had suffered considerable damage over the years. In short, Mr. Duke needed some work, and with the focus of this year’s exhibition, Nature Tamed, on the landscape and gardens at Rough Point throughout its whole long history and under all owners (from Frederick Vanderbilt to NRF), the time seemed right to get Mr. Duke out of storage and onto a visible wall at Rough Point.

A little nip and tuck in the Berkshires

In late February, we sent the portrait and frame to the Williamstown Art Conservation Center (WACC), which shares facilities with the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. At WACC, director Thomas Branchick cleaned the painting, stabilized its canvas support, addressed all other areas of damage, and gave the portrait a new layer of varnish to protect the painted surface. To restore the frame, furniture and frame conservator Hugh Glover replicated several missing pieces of ornate scrollwork and then painted the new surfaces to match the aged appearance of what remained of the original carved and gilded molding.

Mr. Duke returned from the Berkshires on April 4 (fig. 2), and you can now see him on the second floor landing in close proximity to the portraits of wife Nanaline (fig. 3), painted by Sir James Jebusa Shannon (1862-1923) around the time of her marriage to Mr. Duke in 1907, and daughter Doris at age ten or eleven (fig. 4), painted, like the portrait of her father, by the Englishman John Da Costa.

The lasting legacy of Washington Duke, and we’re not just talking about money . . .

In preparing to bring the family back together, we became aware of one of the other portraits of Mr. Duke by John Da Costa – a 1922 oil sketch (fig. 5), now in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., which appears to be a study from life for the Rough Point portrait. Between the 1922 and 1924 portraits, however, Da Costa changed the setting from an impressionistic exterior with blue sky to a non-descript, dark interior. Why the change? We suspect James B. Duke’s father, although dead for 19 years at that point, might still have had something to do with it.

Our portrait is a near identical twin to the portrait of James B. Duke that now hangs in the Gothic Reading Room of the Duke University Libraries (fig. 6). Adjacent to this “twin” is a posthumous portrait of Washington Duke (1820-1905) in the same dimensions and with a similarly dark interior background and red, upholstered chair (fig. 7). Both of the Duke University portraits date to 1924, as does the Rough Point portrait, and all were likely commissioned to commemorate the $40 million donation made by James B. Duke to the Duke Endowment that same year. The Duke Endowment supported several North Carolina colleges, including Trinity College in Durham, which would later be renamed Duke University in honor of Washington Duke’s legacy of giving to the college.

As a model for the posthumous portrait of Washington Duke, Da Costa used a 1904 portrait by Abraham Edmonds (Fig. 8; also now in the Rough Point collection), in which the senior Duke is similarly posed in a dark interior. For visual consistency, it seems that Da Costa simply adapted the Edmonds composition and setting for his portraits of both father and son destined for Duke University, and by extension to the version of the James B. Duke portrait intended for the family. Thus, we have Washington Duke and Abraham Edmonds, both long gone in 1924, to thank for the somber, dark interior.

Not all frames are created equal

There were other benefits to bringing James B. Duke back into the public view. When conservators had a close look at the back of Mr. Duke’s frame they found a stamped maker’s mark: “M. Grieve Co., Hand Carved, New York & London” (fig. 9). Maurice Grieve (fig. 10) relocated his family’s two-century old wood carving business from Belgium to New York in 1906 and closed the shop upon retirement in 1955. His carved and gilded frames represented the pinnacle of the craft and were highly sought after by dealers, collectors, and institutions in the first half of the twentieth century. Most famously, Grieve made the frame for Gainsborough’s Blue Boy after its controversial sale to the American industrialist Henry Huntington in 1921.

Only a few years after making the Blue Boy frame, Grieve was commissioned to carve the frame for John Da Costa’s portrait of James B. Duke, now reunited with the other two family portraits at Rough Point (fig. 11). What young Doris Duke thought of all of this is still a mystery. From the expression captured by John Da Costa (see fig. 4), one might guess there were places she would rather have been than in the artist’s studio.

By Margot Nishimura, Deputy Director for Collections, Programming, and Public Engagement

by NRF User | Nov 2, 2013 | NRF News

Here are some simple things that YOU can do. Start at the top of each section with the least expensive, easy to do items and work your way to the bottom where a little more investment and expertise may be needed.

Systems Basics

• Reduce your AC costs! Put windows to work – cross ventilate, adjust blinds, etc.

• Install programmable thermostats and adjust the settings appropriately as seasons change.

• Set water heaters to 120 degrees, and even less in summer.

• Use thick or padded rugs to insulate bare floors.

• Don’t block hot air or cold return registers with furniture or other barriers.

• Read NPS’s Preservation Brief #3, “Conserving Energy in Historic Buildings”.

• Regularly clean or replace filters in forced air systems and AC units.

• Replace radiator steam vents (1-pipe system) or steam traps (2-pipe system).

• Make sure heating ducts and pipes are well insulated and sealed.

• Place a reflector barrier between radiators and outside wall (particularly if wall is uninsulated).

• Have your furnace or boiler cleaned and serviced regularly.

Stop Air Leaks

• Weather-strip exterior doors and attach “sweeps” to the bottom.

• Caulk cracks and joints around door and window frames.

• Seal leaks in ductwork – that’s what REAL duct tape is for!

• Weather-strip or seal attic doorways and hatches.

• Use appropriate spray-foam to seal cracks in foundations and crawlspaces.

• Use foam backer rod to fill large gaps.

Insulation

• Different types of insulation for different applications; Understand R-values

• Attics are the best place to start with insulation; it can give the best return on investment

and has the least potential to harm the historic fabric of your house.

• Plaster walls can be adequate – leave them alone unless other work is needed.

Windows

• Exterior storms – good investment for energy savings, but also to protect your wood windows!

• Interior “insulating panels” – lower cost alternative, doesn’t impact historic character of exterior facade, but beware of potential moisture issues.

• Most original wooden windows can be retained and repaired, resulting in a snug fit and increased energy savings. For more information see other tip sheets in this packet.

Information provided by the Collaborative for Common Sense Preservation :

Historic New England

Preserve RI

Newport Restoration Foundation

by NRF User | Feb 16, 2013 | NRF News

These sites will you help you understand how to address the flow of air and moisture through your home’s “envelope” (its roof, exterior wall, and foundation). Take some easy steps to save money, help the planet, and improve the comfort of your home.

Detecting Air Leaks

This concise guide describes how to find air leaks (or drafts) in your home.

www.energy.gov/energysaver/articles/detecting-air-leaks

Sealing Air Leaks

Once you have located areas in your home where comfortable air is escaping or unwanted air is flowing in, these U.S. Department of Energy sites offer easy tips for sealing those leaks. (Please note that while the Collaborative for Common Sense Preservation concurs with this site’s endorsement of storm windows, we typically do not recommend the other suggestion of replacing your windows.)

www.energy.gov/energysaver/articles/tips-sealing-air-leaks

www.energy.gov/energysaver/articles/caulking

Weather Stripping

Air sealing around windows and doors increases your comfort and saves energy. This site provides a comprehensive list of weather-stripping options, the advantages and disadvantages of each, and tips for installation around windows and doors.

www.energy.gov/energysaver/articles/weatherstripping

Assembled by the Collaborative for Common Sense Preservation (Historic New England, Newport Restoration Foundation and Preserve Rhode Island).