A small painting in a gilded frame hangs above the mantle in Doris Duke’s bedroom at Rough Point. Amidst the splash of yellow walls, bold purple fabrics, and glinting mother of pearl furniture, the painting is unassuming by comparison. This is why visitors are often surprised to discover that it is one of the more precious works of art in the house—a charming scene of a young girl focused on her needlework, painted and signed by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the famous French Impressionist.

Until recently, very little was known about this wonderful, but mysterious, painting in Rough Point’s collection. As this summer’s Laird Graduate Intern in Museum Studies, I’ve had the opportunity to dive deeply into research on both the house and its collection, and I found myself especially captivated by this little painting.

A pair of paintings

One of the most exciting discoveries in my research revealed that our painting is most likely a preparatory study for another Renoir owned by The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. The resemblance between the two paintings is readily apparent. The compositions are nearly identical, with the model—who is now known to be Nini Lopez, one of Renoir’s favorite Montmartre girls—calmly engaged in needlework as her blouse falls gently off one shoulder. Our painting has a loosely worked quality, capturing the artist’s inspiration in the moment.

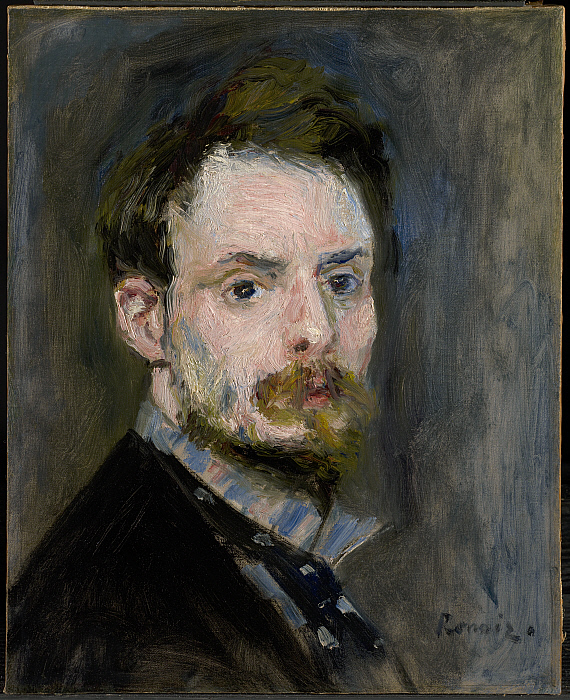

The period of the 1870s was a transformative time in Renoir’s life and work. Living in poverty and rejected by many critics, Renoir struggled to gain a professional foothold. Even among the other Impressionists, Renoir’s pure colors and broken brushstrokes were not always understood—in fact, Manet once said to Monet that Renoir would never amount to anything.[1] But soon after our painting was completed in 1875, things started to pick up for Renoir. With portrait commissions from wealthier patrons, such as the Charpentier family in 1878, Renoir could now afford to marry and buy a house.[2] His style was also maturing. Renoir’s fascination with girls engaged in needlework continued throughout his career, perhaps stemming from his insistence that his style of painting was tricotage, or knitting the colors together on the surface.[3]

A “poetic symbol” in times of war

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Self-portrait, c.1875, The Clark Art Institute, 1955.584.

In 1919, the painting was part of a significant collection of nineteenth-century art put up for auction by the estate of its previous owner, Nicolas-Auguste Hazard. Alongside our Renoir were works by other titans of nineteenth-century painting, including Cezanne, Delacroix, Courbet, Gauguin, and Manet—perhaps finally proving just how wrong Manet had been about Renoir’s potential. In a twist of fate, Renoir died on December 3, 1919—the final day of the auction.

By 1941, the painting had passed through several hands and was now part of the war effort. France had fallen to Hitler and organizations formed across the United States to send aid to Europe. One such organization, the Free French Relief Committee, held a Renoir exhibition to raise money for General de Gaulle’s nascent French Resistance.[4] They chose Renoir because 1941 was the 100th anniversary of his birth, and because they believed his art to be revolutionary, “a poetic symbol” of the France that the men and women of the Resistance were fighting for.[5] Our painting appeared in the exhibition alongside eighty-eight other works by the artist. The exhibition closed on December 6, 1941. The very next day, December 7, the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor finally forced American involvement in World War II, which eventually led to the liberation of France and the end of the war.

Home at last

Like Renoir, Doris Duke had a zest for life. She acquired the painting in 1957 and later installed it as the only painting in her bedroom, where its bright, vivacious colors perfectly complemented the eclectic, bold design of the room. Today, Jeune fille blonde cousant remains a cherished object in the Rough Point Collection, delighting visitors with its soft, dream-like quality—the hallmarks of Renoir’s style which make it such a pleasure to behold.

Photograph of Doris Duke’s bedroom, Rough Point, Newport Restoration Foundation

By Ashley E. Williams

Ashley E. Williams is the Newport Restoration Foundation’s Laird Graduate Intern in Museum Studies for summer 2017. During her summer at Rough Point, Ashley dove deeply into curatorial research and provided support for programming and events. In addition to creating fuller object files for several of our most prominent paintings, her larger research project explored the architectural and public history of Rough Point from 1887 to 1924. This fall, Ashley goes on to her final year at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, where she is earning her Master’s degree in the History of Art and Architecture.

Sources:

[1] R.H. Wilenski, Modern French Painters (New York: Reynal & Hitchcock, 1940), 61.

[2] Ibid., 62.

[3] Renoir: Centennial Loan Exhibition 1841-1941, For the Benefit of the Free French Relief Committee, (New York: Duveen Galleries, 1941), 18.

[4] Coincidentally, the committee included Grace Graham Wilson Vanderbilt, a relative of Frederick W. Vanderbilt who built Rough Point (1887-1891), the painting’s final home.

[5] Renoir: Centennial Loan Exhibition 1841-1941, 11.